SHA2017 CTF - Stack Overflow

12 Aug 2017| Event | Points | Solves | Categories | Task ID |

| SHA2017 CTF | 100 | 155 | Crypto | 4432 |

Challenge Description

I had some issues implementing strong encryption, luckily I was able to find a nice example on stackoverflow that showed me how to do it.

stackoverflow.tgz b245e83f0fb65763b3c1b346813cb2d3

Overview

The archive contains a file named flag.pdf.enc which is just composed of random bytes and a python script called encrypt.py:

import os, sys

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

fn = sys.argv[1]

data = open(fn,'rb').read()

# Secure CTR mode encryption using random key and random IV, taken from

# http://stackoverflow.com/questions/3154998/pycrypto-problem-using-aesctr

secret = os.urandom(16)

crypto = AES.new(os.urandom(32), AES.MODE_CTR, counter=lambda: secret)

encrypted = crypto.encrypt(data)

open(fn+'.enc','wb').write(encrypted)So we specify an input file (in our case flag.pdf) which is encrypted by the python script using AES. We look up the AES.new function here to understand the initialization:

- We choose 32 bytes of random for the AES key

- We use AES in counter mode

- We use a lambda expression to create a function that returns a series of counter blocks based on a block of 16 randomly chosen bytes

Wait, the last point seems pretty odd. The function is supposed to implement a counter, instead the same 16 bytes are repeated infinitely. To explain why this is a problem and how we can leverage this behavior to reconstruct the encrypted PDF file, we first have to explain how the counter mode works.

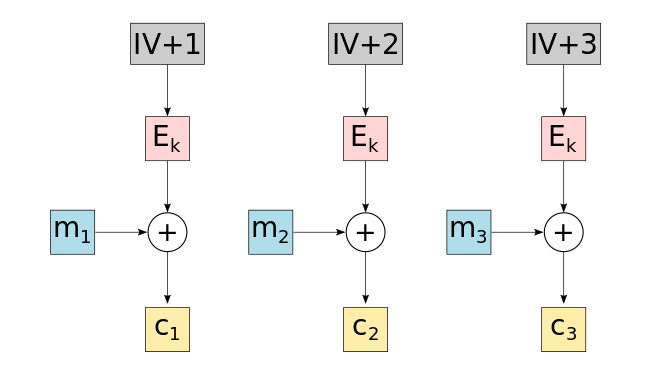

Counter Mode

Block ciphers (such as AES) are able to encrypt or decrypt a single block of fixed length. Therefore, we need to specify modes of operation that dictate how inputs that are longer than a block size are being processed. Every mode of operation chains together multiple applications of the block cipher transformation to process larger inputs. The counter mode does this by successively encrypting a counter value and using the resulting ciphertext blocks as a keystream, which essentially turns the block cipher into a stream cipher. The plaintext is then simply XORed with the keystream for encryption. Decryption works analogously as we only need to reproduce the same keystream and can perform an XOR on the ciphertext to recover the plaintext.

The counter is typically implemented by using a publicly known initialization vector and incrementing it:

- Ek: Block cipher (e.g., AES) with key k

- m1, m2, … : Plaintext message blocks

- c1, c2, … : Resulting ciphertext blocks

- IV: Initialisation vector used for the counter

Note that by turning the block cipher into a stream cipher we have to make sure that the security requirements for a stream cipher are met. The most important requirement is that the keystream is not allowed to ever repeat itself. Otherwise, an attacker can XOR the ciphertext parts where the key repeats itself and obtain the XOR of the two plaintexts:

C1= P1 XOR K

C2= P1 XOR K

C1 XOR C2= (P1 XOR K) XOR (P2 XOR K)= P1 XOR P2The Python package Crypto allows us to specify a custom counter function. Unfortunately, this freedom can be abused to implement very insecure counter functions such as counter=lambda: secret. With secret being only 16 bytes long, we basically subverted the whole security of AES and reduced it to a repeating 16 byte long stream cipher key. All we have to do now is to XOR the ciphertext parts that were encrypted under the same key and guess some plaintext. While guessing plaintext is pretty pointless against a properly used stream cipher, it makes sense in this scenario since we have a method of validating our guess. Let’s use the example from above and pretend we are guessing what P1 could be. Since we have access to P1 XOR P2, we can check our guess (let’s call it P1’) by calculating P1' XOR (P1 XOR P2) and see whether P2 makes sense or not. If so, we probably guessed the correct plaintext for P1. Once we successfully did that, we can extract the key by simple calculating C1 XOR P1= K

Guessing some plaintext using OTP PWN

The process described in the above section is greatly facilitated by the otp_pwn utility, which allows us to interactively check plaintext guesses (and do other cool stuff like crib dragging). We known from the source code that the length of the repeating key is 16 bytes, which is all the information we need to start using the tool:

python otp_pwn.py flag.pdf.enc 16

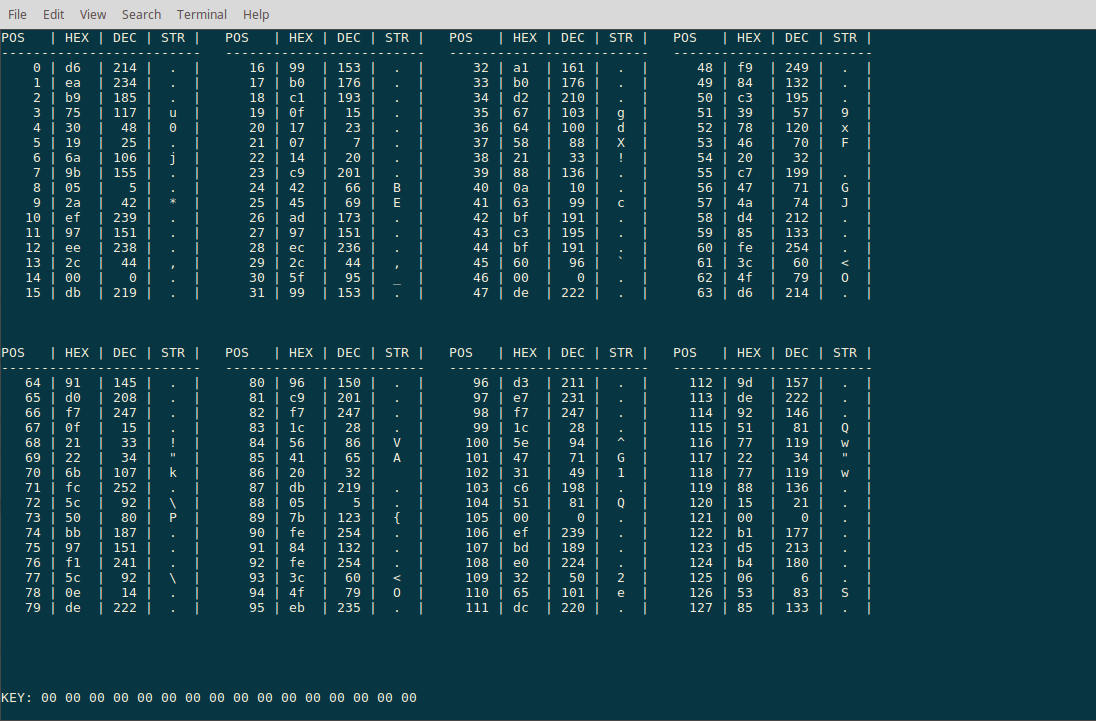

We are presented with an overview of the encrypted file:

The file contents is split up in blocks of the size of the key length, so each block is encrypted with exactly the same key. This allows us to quickly check whether a plaintext guess was correct as we can see whether the resulting key changes produce valid plaintext in the other blocks or not.

So, we know from the filename that we are probably dealing with an encrypted PDF file. We know that most PDF files start with %PDF-1., so let’s apply that plaintext guess with the command :p 0 %PDF-1.:

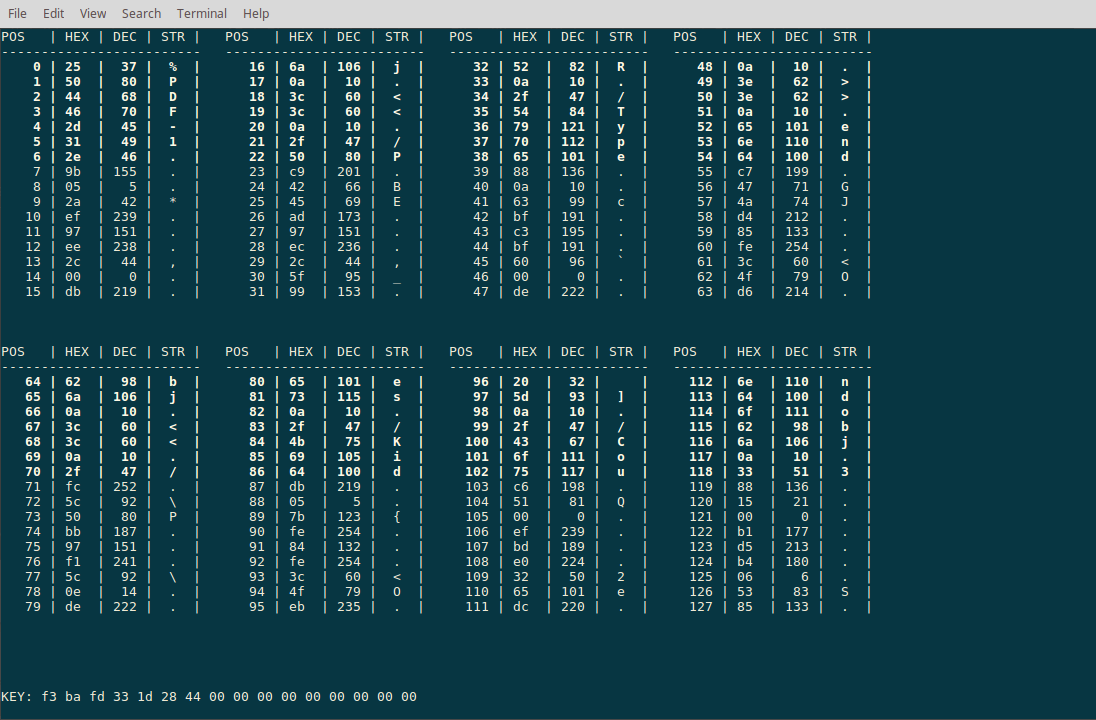

Looks like we guessed correctly! The tool shows the key that resulted from the plaintext input and highlights in bold all positions that the key has been applied to. We study the PDF file specification a bit more and quickly find out that the position 21 and 22 are probably the beginning of the /Page directive. So we type in the command :p 23 age and indeed, the rest of the blocks decrypt correctly as well. We continue guessing plaintext where we already decrypted the start of a command and are quickly able to recover each part of the key: f3 ba fd 33 1d 28 44 a8 25 20 de b7 de c0 6f b9. We dump the decrypted file using the command :d flag.pdf and take a look:

Agreed, Stack Overflow is a nice place but always make sure you understand what you are copy and pasting!

The flag is: flag{15AD69452103C5DF1CF61E9D98893492}